Illustration by Jamiel Law

Resolving Reparations

Compensation to redress the wrongs of slavery is gaining momentum, but determining who will pay how much to whom is complicated.

BY ELAINE MCARDLE

Not that long ago, the idea of reparations for Black Americans as redress for the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow murders and other institutional racism was widely regarded as a fringe effort unlikely to ever see the light of day. Times have changed.Last year, Evanston, Illinois, became the first city in the US to provide reparations to Black Americans, paying $25,000 to each qualified person to atone for widespread discriminatory housing practices. The money — funded through private donations and a sales tax on cannabis — can be used for mortgage payments, a down payment on a home or home repairs.

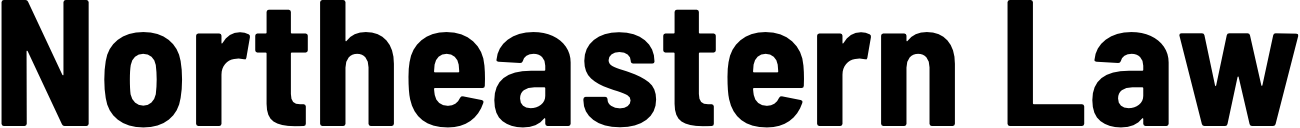

Professor Margaret Burnham

Photo by Mark Ostow

Some of this disparaging focus on who’s going to pay and who’s going to receive has the effect if not the intention of obscuring the enduring thrust of the reparations movement…

Building Consensus

Today, a growing number of reparations projects are underway in cities across the country. “This is a movement.These projects are moving forward, and there’s no stopping them,” says Professor Margaret Burnham, founder and director of Northeastern Law’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project (CRRJ), which over the past 15 years has investigated more than 1,000 cases of previously undocumented Jim Crow-era racial homicides. Burnham was also recently appointed director of reparations and restorative justice initiatives for the law school.

But even among reparations supporters, there is no consensus on how they should work. William A. Darity Jr., a professor of public policy and expert on African and African American studies and economics at Duke University and a national voice on the issue, believes that the standard for reparations payments should be the racial wealth gap and that payments should come only from the federal government.

Systemic racism, from slavery through to more recent denials of federal housing and education programs, denied. Black families opportunities to build wealth, he explains. In 2019, the average Black household had $840,900 less in net worth than the average white household, according to the Federal Reserve. That constitutes approximately $350,000 per person, so Darity argues that $350,000 should be paid to each of the 40 million Black Americans whose ancestors were enslaved in the US — more than $14 trillion. The combined budgets for all state and local governments are less than $5 trillion, and for that reason, and to maximize equity and fairness, it’s up to the federal government to pay this debt, he argues.

“My deepest fear about local reparations is you’ll have this patchwork of piecemeal programs that won’t come anywhere near eliminating the racial wealth gap, but people will then say there’s no need for a federal program because ‘You already have reparations,’” says Darity, co-author of From Here to Equality: Reparations for Black Americans in the Twenty-First Century.

But Burnham strongly disagrees. State and local efforts are gaining momentum; federal efforts have gotten nowhere and are unlikely to, given the current deeply polarized Congress. Moreover, she emphasizes, “the reparations movement is about more than who’s going to get what and when. There are a thousand questions that can and should be raised, but you have to recognize that some of this disparaging focus on who’s going to pay and who’s going to receive [reparations] has the effect if not the intention of obscuring the enduring thrust of the reparations movement, which is to appreciate that this history is a part of American history.”

Expanding the Conversation

While the reparations movement is gaining momentum, it’s anything but new. In 1783, a formerly enslaved woman, Belinda Royall, successfully petitioned the Massachusetts General Assembly for a pension from her enslaver’s estate to repay her for her uncompensated labor. And since 1988, Japanese Americans have received more than $1.6 billion in reparations related to their internment during World War II. But reparations for Black Americans have proven quite elusive. In 1989, a federal bill, H.R. 40, sought to create a commission to recommend remedies for the harm caused by slavery and later racially discriminatory policies, but it has languished for more than 30 years.

Supporters now have renewed hope for its passage. Two decades ago, only 4 percent of white Americans supported reparations for Black Americans, according to a 2000 study by University of Chicago scholars. By 2021, that number had grown to 28 percent of white Americans and 86 percent of Black Americans, according to a national poll conducted by the University of Massachusetts Amherst/WCVB.

The push for reparations isn’t limited to the US or Black Americans, but is a global movement “quickly becoming a norm in the international human rights lexicon,” Burnham says. She points to support within the United Nations for redressing the past ills of slavery and colonialism worldwide and also to repay small island states for the current existential threat from climate change.

And the murder of George Floyd in 2020 fostered a new understanding of systemic oppression, Burnham says, and sparked new discussions on how reparations can help right past wrongs. “People are now understanding this as the centerpiece of a movement around rights for all marginalized groups: trans people, LGBTQ+ people, undocumented people and others,” she says.

For CRRJ, which has engaged in efforts to get redress for particular families who lost loved ones to Jim Crow-era violence, a broader look at the reparations movement became a focus about five years ago. Localities across the country were beginning to grapple with the idea of reparations, but the issue is very complex: Who should get reparations? What form should reparations take? Who will pay for them?

“We felt there was a need for broader state engagement in this project,” says Burnham, the author of the award-winning book By Hands Now Known: Jim Crow’s Legal Executioners. Solutions will likely look different in each locality based on its governmental structure and what the community is looking for, she notes. “We can at least help them think through the questions they need to ask and to understand what other communities are doing.”

CRRJ’s first major step was to host a series of national discussions and conferences on reparations. In 2020, it presented an all-star roster of reparations experts, including the current champion of H.R. 40, Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Tex.), and Ta-Nehisi Coates, author of the deeply influential 2014 Atlantic article “The Case for Reparations.” CRRJ realized that it could play a critical role in supporting stakeholders and policymakers with essential legal and policy guidance: in 2021, it launched the Racial Redress and Reparations Lab to provide historical research, analytical data, convening and meeting spaces, educational programming and consultation. CRRJ’s Burnham-Nobles Digital Archive holds evidence collected by more than 400 Northeastern law and journalism students and their faculty demonstrating the extensive scale and scope of killings between 1930 and 1954 in the Jim Crow South.

“Part of the reason for the archive is building that evidence for what happened and the through line from slavery to Jim Crow to the present,” says Katie Sandson,

the lab’s former project director. “Having it captured in a way that can’t be denied is important when having conversations” about reparations.

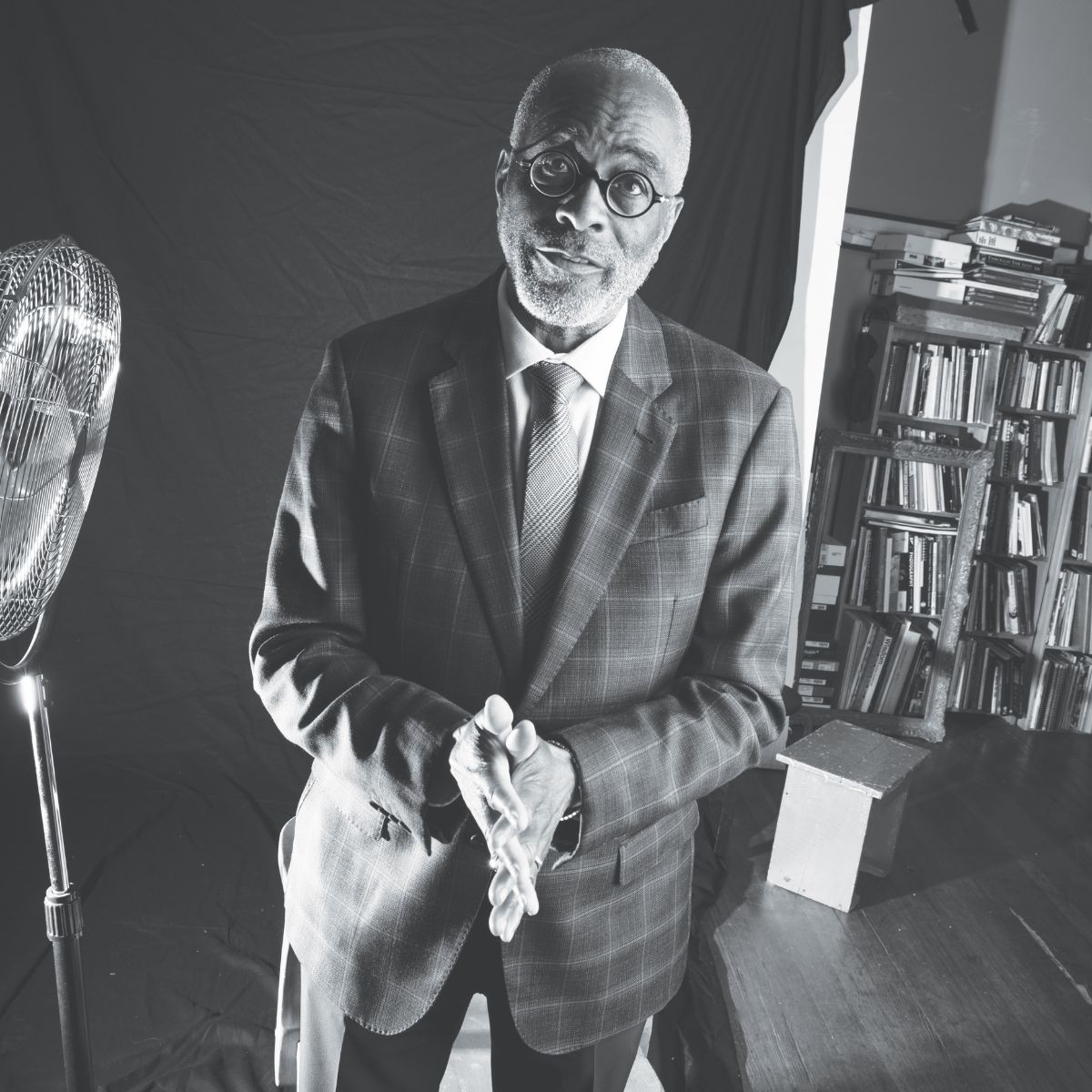

Joseph D. Feaster Jr. ’75

Photo by Mark Ostow

The Government of Boston, individuals and institutions in Boston historically benefitted from obtaining free labor from Black people and denying Black people opportunities afforded to whites

Establishing Facts

Northeastern Law graduates and students are involved in reparations in a number of other ways. CRRJ offers a universitywide course, Historical Injustice and Reparations, that broadly examines the movement. “We think about reparations projects both at the corporate level — banks, insurance companies, for example — and at the state level, in terms of what cities and states and the federal government should be doing in this arena,” says Burnham. Boston Mayor Michelle Wu recently created a Task Force on Reparations and named Joseph D. Feaster Jr. ’75 as its chair. Feaster, who has decades of service in the fight for civil rights, including as past president of the Boston branch of the NAACP, says the task force will examine Boston’s participation in the institution of slavery, dive into historical data and hold listening sessions with the community before presenting recommendations to the mayor and city council. “The government of Boston, individuals and institutions in Boston historically benefitted from obtaining free labor from Black people and denying Black people opportunities afforded to whites,” says Feaster. “I applaud Mayor Wu and the city council for addressing reparations at this critical time.”

On the West Coast, Mills College at Northeastern University, in collaboration with UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, recently launched the Black Reparations Project. Co-chaired by Dr. Erika Weissinger and Dr. Ashley Adams, it will create opportunities for stakeholders to study, discuss and collaborate on policies related to Black reparations, reinforce connections between leaders in Black reparations movements, promote public awareness and education on the history and need for Black reparations, and provide a platform for the development and implementation of effective reparations policies in California and beyond, says Weissinger. In particular, it is also engaging in research related to Black reparations in the areas of housing and historic preservation, with more projects to come, adds Adams.

Max Bloodgood ’24

Photo by Mark Ostow

The law has the potential to to do something about the harm that we have caused in the past and to recognize that harm still exists today and still affects people.

Last summer in Boston, Max Bloodgood ’24 completed a co-op at CRRJ’s reparations lab, assisting Sandson in cataloging the state and local reparations landscape, the only effort they’re aware of that is tracking these projects. The lab is including all forms of reparations, from direct payments to recipients to the funding of historical markers that recognize incidents of racial violence to international models for healing after societal trauma. “The law has the potential to do something about the harm that we have caused in the past and to recognize that harm still exists today and still affects people,” says Bloodgood, who’s interested in LGBTQ+ rights and civil rights broadly. “I think that it’s an acknowledgement that the world we’re living in is extremely connected to and shaped by the past.”

In March, CRRJ hosted a discussion, “Building the Record for Reparations,” which included several key figures in the reparations movement in Canada, Rhode Island and California. The California Reparations Task Force has worked for two years and in June submitted final recommendations to the state legislature; according to recent reports, it could recommend a payment of $1.2 million to each descendant of slavery living in California. New York also recently created a commission to study reparations for Black people.

In 2020, Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza created a process of truth, reconciliation and municipal reparations for Black and Indigenous people and people of color. Keith Stokes, vice president of the 1696 Heritage Group, a historical consulting firm that is dedicated to helping persons and institutions of color to increase their knowledge of their unique American heritage, is a key member of the effort.

“In the 20th century, redlining, urban renewal and housing and employment discrimination had as much impact as enslavement,” Stokes said at the CRRJ panel discussion. The next step is for the city to work to close the wealth and equity gaps through investment in Black businesses, creation of a Black public policy center and investments in education, including creating a statewide African American history curriculum, Stokes added.

With so much activity, the tensions in how to structure this vast and complicated movement continue to play out, but even among those who disagree on how to provide reparations, supporters agree that things are moving in the right direction. “I’m absolutely convinced the increasing knowledge about America’s history has really had an effect on people’s attitudes toward reparations,” says Darity.

“The conversation that’s been generated around how to do reparations is a conversation about American history,” Burnham agrees. “So, it’s going to produce a broad array of results, some of which we can perhaps visualize today — and many which we cannot imagine at present.”

Focusing too much on the many specifics — who will get reparations, who will pay for them — will block the opportunity for Americans to face their history, argues Burnham. “You foreclose that conversation by moving too quickly to who is deserving,” she warns.

In the meantime, CRRJ, in partnership with the law school’s Center for Law, Equity and Race (which Burnham also co-leads), continues to produce fact-based data to support reparations, to address legal questions such as the constitutionality of reparations, to identify stakeholders and constituents and to help them structure means and methods that work for localities. “That kind of teaching, learning and research is so critically important today in our country,” says Burnham. “The movement is as much about the why as the how, and if you get tied up in the how then you are missing the opportunity to explore the why.”

About the Author

Elaine McArdle, based in Saratoga Springs, New York, is a contributing writer.

Share

Northeastern Law’s Center for Law, Equity and Race (CLEAR), in collaboration with Suffolk University’s Center for Restorative Justice (CRJ), recently held the commonwealth’s first-ever training in community-centered restorative justice practices for Massachusetts state court judges.

For the second time in two years, Northeastern Law’s Program on Human Rights and the Global Economy (PHRGE) submitted testimony to the Massachusetts General Court’s Joint Committee on Public Safety and Homeland Security in support of the proposed Safe Communities Act, which seeks to protect the civil rights and safety of all Massachusetts residents by limiting the involvement of local law enforcement officers in federal immigration enforcement.