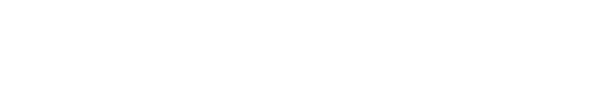

Illustration by Brian Stauffer

Shattered

Thousands of innocent people are languishing in our nation’s prisons. Picking up the pieces is where Northeastern lawyers come in.

BY TOMAS WEBER

It was a few days before Christmas 2018, and Sean Ellis was standing amid a scrum of journalists, TV camera operators and supporters in a strip-lit hallway in the Suffolk County Superior Court. Ellis, then 41 years old and flanked by his attorneys, was clinging tightly to his mother, Jackie, who was clasping Ellis’ tan suit jacket firmly in her fists. It was as if neither mother nor son could quite be sure he would not soon be dragged back to the prison where he’d already spent half his life. “I’m so thankful he’s free,” Jackie said to the press gaggle. “It’s been a long haul.”

Ellis’ conviction for the 1993 murder and armed robbery of a Boston police detective, John Mulligan, had been vacated in 2015 by Suffolk County Superior Court Judge Carol Ball ’76. The case involved a planted gun and doctored ballistics. Three trials and several appeals. Prosecutorial misconduct and police corruption. Perjury and misidentification.

“It was an experience that was beyond words,” says Ellis. “I was always hoping my parents or my loved ones would come to my aid. But they were helpless. And I didn’t know what to do.”

But after a quarter of a century, the Suffolk County district attorney finally dropped the charges — which allowed Ellis to dedicate his life to helping others. In 2020, he co-founded the Exoneree Network, part of the New England Innocence Project (NEIP), where he advocates for the interests of exonerees as well as supporting their practical, emotional and spiritual needs as they reenter society. “Sean didn’t let his trauma define him,” says Professor Daniel Medwed, a criminal law expert who focuses on overturning wrongful convictions. A board member at the NEIP, which investigates wrongful convictions and represents the innocent, Medwed now regularly partners with Ellis to promote the NEIP’s mission and programs. “Sean’s a shining example of how to move forward from tragedy with grace.”

Being framed for the murder of a police officer made Ellis’ case unusual. But according to Medwed, who is the author of BARRED: Why the Innocent Can’t Get Out of Prison, published in 2022, and represented many wrongly convicted prisoners as a practicing attorney before becoming an academic, several aspects of Ellis’ story are “sadly all too familiar.” The case of Ellis, a young Black man wrongly accused of killing a white person, is emblematic of deep problems in the US justice system. And the long and tortuous legal process that Ellis endured, filled with highly restrictive procedural rules, is familiar to many innocent prisoners in the United States who are struggling to be free.

Sean Ellis’ harrowing story has been widely covered in the press and is the focus of a Netflix documentary, Trial 4.

Photo by Mark Ostow

I was always hoping my parents or my loved ones would come to my aid. But they were helpless. And I didn’t know what to do.”

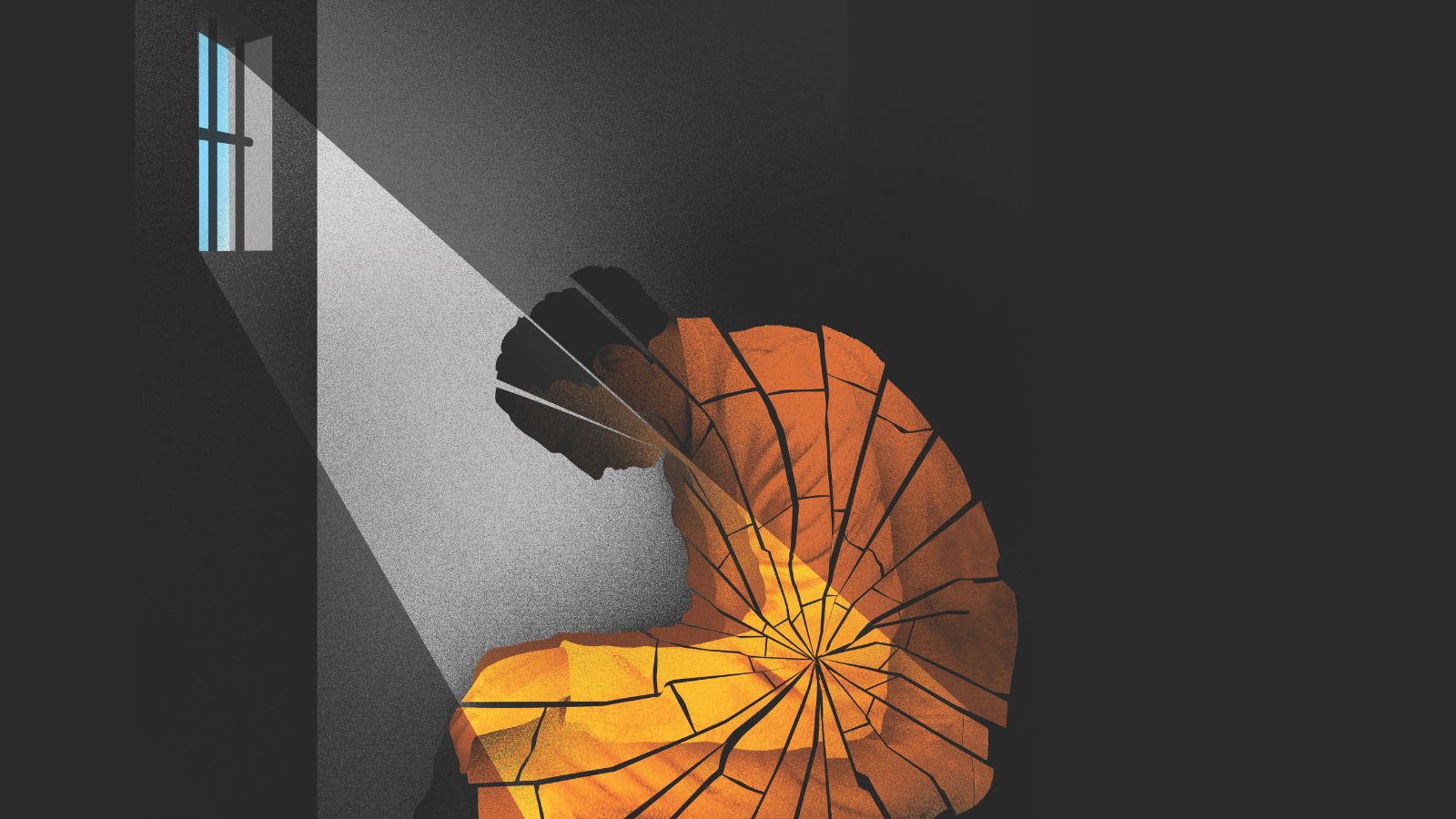

Rush to Judgment

It is estimated that between 0.5 and 2 percent of all convictions in the United States are wrongful. Given the enormity of the nation’s carceral population, that means tens of thousands of innocent people are languishing in US prisons. And with the law stacked against the wrongly convicted, freeing them is a daunting ordeal. “I often liken this work to being handed a box of broken glass and told it was once a window,” says Ira Gant ’10, a criminal defense attorney in Boston who worked for seven years challenging wrongful convictions at the Innocence Program at the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS), Massachusetts’ public defender agency. It’s the lawyer’s job to put it back together — “but then,” says Gant, who now serves as forensic services director for CPCS, “you begin to realize key pieces are missing.”

It’s a painstaking puzzle Medwed knows well.

At the turn of the millennium, Medwed was running the day-to-day operations of an innocence project at Brooklyn Law School when he opened a letter from Stephen Schulz, who was then embarking on an 11-year sentence at a New York state prison. Medwed, surrounded by towers of precariously balanced case files, read that Schulz had just been convicted of robbing a Long Island restaurant at knifepoint. But Schulz insisted he hadn’t left his apartment that evening. The crime, Schulz believed, was in fact the work of his doppelgänger: a tall, heavyset white man by the name of Anthony Guilfoyle. Guilfoyle, who had Schulz’s puffy cheeks and scruffy hair, had pled guilty to a string of similar robberies in the area during the same period. Could Medwed help?

Looking the case file over, Medwed pinpointed some issues. When two witnesses picked out Schulz from a photo lineup, police settled on him as the suspect immediately — even though there was nothing in Schulz’s record to indicate violent tendencies.

It’s a widespread problem. “Police and prosecutors come under immense pressure to rush to judgment,” says Medwed. Police officers have arrest quotas. And when they believe that the evidence points to a particular defendant, the responsibility for errors is often passed up to prosecutors.

“The police seem to think, Surely the prosecutors will screen this if there’s a mistake,” says Medwed. But prosecutors tend to foster cozy relationships with the police and have strong incentives to keep them onside. “Once the police arrest you, once prosecutors charge you,” says Medwed, “your presumption of innocence gets frayed.”

Upon seeing Schulz in person for the first time, one of the two witnesses again misidentified him; the other testified that he was not the robber — the robber was taller and heavier. (Guilfoyle was, in fact, taller and heavier than Schulz.) Yet the jury believed the first witness over the second and returned a guilty verdict. Of wrongfully convicted people, 70 percent are victims of witness misidentification, and juries, says Medwed, are often unaware that evidence relied on by prosecutors can be fallible. Identifying a suspect, he says, is much harder than many juries think. Crimes tend to occur quickly and at night, without warning. Evidence suggests people are particularly bad at identifying others across racial lines. And “if somebody puts a knife to your throat,” he says, “you’re concerned with the knife, not the person.”

Professor Daniel Medwed’s book, BARRED: Why the Innocent Can’t Get Out of Prison, has won accolades and honors for its persuasive call for change.

Photo by Mark Ostow

Once the boulder is at the bottom, it’s really, really hard to push it back up.”

Arguing With Conviction

After conviction, everything gets vastly more difficult. “The presumption of innocence,” says Medwed, “flips to a presumption of guilt.” The criminal justice system emphasizes finality, and for the defense, reversing a guilty verdict is a Sisyphean task. “Once the boulder is at the bottom, it’s really, really hard to push it back up.” Although there are opportunities to challenge convictions, “these are flawed in so many granular ways,” he says. Schulz’s case epitomizes the problem.

At trial, Schulz’s attorney was blocked from showing the jury a picture of Guilfoyle. Seeing how closely Schulz resembled the local convicted robber might have raised doubts about whether he was the right man, but on appeal, the court refused to accept that the trial judge had misapplied the rules. And even when trial judges make serious errors, Medwed says, verdicts are upheld if they did not “abuse their discretion” — a tough bar to clear. After Medwed took over the case, he started uncovering fresh evidence. The restaurant’s cook, he discovered, was facing a weapons charge that mysteriously vanished once he agreed to say Schulz was the robber. Medwed obtained affidavits from the robbery victim stating she was almost certain Guilfoyle was the culprit. He tracked down Schulz’s roommate, who confirmed Schulz’s alibi.

He submitted it all to a New York state court and asked the judge to throw out the conviction. It still wasn’t enough. “Even with all of this new evidence,” says Medwed, “not only couldn’t we get a new trial, but we couldn’t even get the judge to grant a hearing on whether to get a new trial.” It was a frustrating lesson on the weight that the rules place on guilty verdicts.

In 2007, Schulz was finally released following a habeas corpus petition in federal court. The judge ruled that the trial attorney had violated Schulz’s constitutional right to effective counsel by not interviewing the victim. The judge made it clear he was not ruling that Schulz was innocent. The whole process had taken eight years — the majority of Schulz’s wrongful sentence.

Ira Gant is an attorney with CPCS, teaches about wrongful convictions and forensics, and has helped free multiple innocent men.

Photo by Mark Ostow

I often liken this work to being handed a box of broken glass and told it was once a window.”

“There’s no right to a speedy trial in a post-conviction context,” says Gant. Often, post-conviction cases get bumped to make room for more “urgent” matters — precious time that the innocent will never get back. In 2009, another client of Medwed’s, Fernando Bermudez, who spent 18 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, was finally exonerated at the age of 40. “I’m still trying to overcome the damage done to me,” says Bermudez.

“They took some of my best years.” Schulz lost time — and because he was unable to fully clear his name, his reputation was permanently damaged. Unable to access compensation, he now lives a life of near poverty in a motel.

Medwed found the conclusion to Schulz’s case infuriating — one of the many frustrations that, he says, drove him to write his book. “I thought that by publicizing these issues, I could do more good in the long run,” he says, “by provoking a change in the procedures and rules.” Medwed is pushing for change in other ways, too. He helps shape the strategy of the New England Innocence Project, which, like the CPCS Innocence Program, has close ties with Northeastern Law. Students regularly work there for their co-ops. “It was really amazing,” says Princess Diaz-Bîrca ’23, an attorney at Berney & Sang, a civil rights law firm in Philadelphia, about her co-op experience with the CPCS Innocence Program, “to meet people who continue to not only advocate for themselves but who have created a community and continue to uplift others.” She noticed that many exonerees who, like Schulz, had not been declared factually innocent by the court, suffered from constant anxiety. “They felt as if all of a sudden,” she says, “they could end up back in prison.”

Working on innocence cases places future attorneys close to open wounds and raw trauma, but Medwed also sees how the unique opportunity enriches his students. They learn just how long it takes to investigate and build a case — and they come to understand the disappointments and frustrations inherent in this type of work. “As Martin Luther King Jr. said, the arc of history bends toward justice,” says Medwed, “but that arc tilts very gradually. It takes a very long time. This work shows the power of developing a case slowly, prevailing step by step and changing hearts and minds.”

About the Author

Tomas Weber is a reporter based in London, England.

Share

Meghan Leong ’25, a dedicated educator and advocate committed to equity and justice, has been named as the second recipient of the annual Tyler Lawrence Memorial Peacemaker Award.

Professor Margaret Burnham, founder and director of Northeastern Law’s Civil Rights and Restorative Justice Project, spoke at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Conference in Austin, Texas, in March about policing and modern-day lynchings in the rural South.

A judiciary representative of the population it serves is a fundamental necessity, says Justice Ramon Ocasio III ’88.