Illustration by Curt Merlo

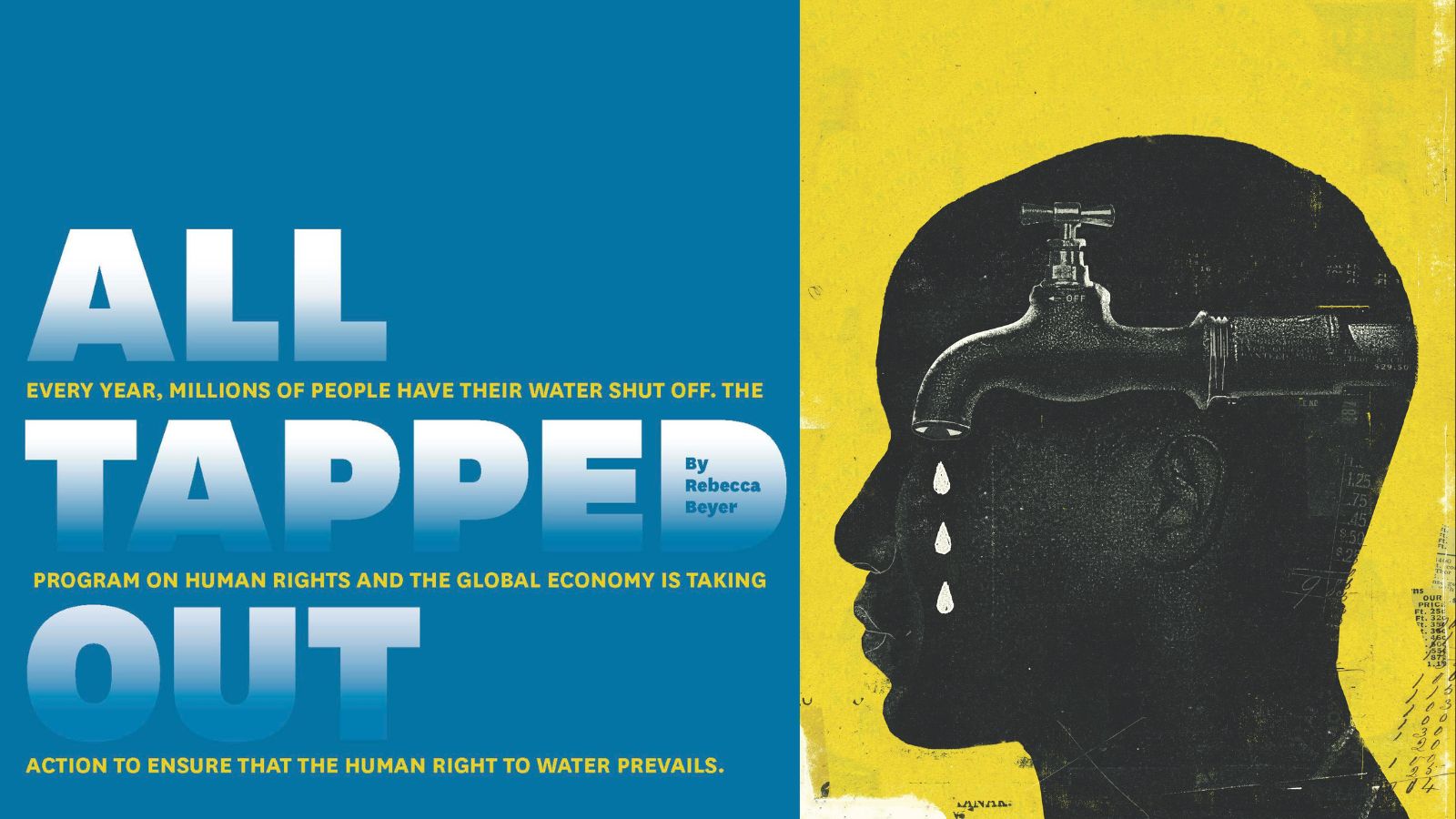

All Tapped Out

Every year, millions of people have their water shut off. The Program on Human Rights and the Global Economy is taking action to ensure that the human right to water prevails.

BY REBECCA BEYER

Most Americans take for granted that when they turn on the taps in their homes, clean water will come out. But each year in the United States, utility companies shut off water to millions of people who cannot afford to pay their bills, a drastic measure that can lead to illness, foreclosure and even the removal of children from their parents’ care.

Comprehensive data on water shutoffs is hard to come by, making the problem even harder to address. But, based on a 2016 first-and-only-of-its-kind survey, the nonprofit Food & Water Watch now estimates that in a typical year, 15 million people in the US experience a shutoff for nonpayment.

A water shutoff isn’t just a penalty; it’s a violation of people’s human rights. For nearly 10 years, Professor Martha Davis, a faculty co-director of the law school’s Program on Human Rights and the Global Economy (PHRGE), has fought against shutoffs and for water access and affordability more generally. One of her earliest efforts came in Detroit after that city shut off water in 2014 to approximately 30,000 people who had not paid their bills. In the ensuing litigation, Davis joined other human rights advocates to argue in an amicus brief that the shutoffs violated several international human rights treaties. Since then, she has worked on water and sanitation issues in places ranging from Somerville to Sweden.

Professor Martha Davis

Photo by John Soares

Delaying access to clean water comes with serious consequences.”

The human right to water and sanitation was explicitly recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010, but, as is the case with so many human rights, roadblocks to recognition and implementation abound. PHRGE and other advocates across the nation (and world) are fighting to make water more affordable and accessible, including through increased information from water utilities themselves. Davis and her team at PHRGE argue that without more knowledge about how many people — and which communities in particular — are most impacted by an inability to pay their bills, the problems can’t be meaningfully addressed.

The stakes could not be higher.

“Water is a basic necessity,” says Davis, chair of the expert committee for the Human Right 2 Water, an international organization that works to integrate the human rights to water and sanitation into law, policy and practice. She is also co-author of Human Rights Advocacy in the United States, the first law school textbook focused on domestic human rights enforcement. “Delaying access to clean water comes with serious consequences.”

There are also racial inequities in water access. In October, Davis and two Northeastern Law students, Jennifer Loveland-Rose ’25 and Zain Walker ’24, traveled to Geneva to present a report to the UN Human Rights Committee on behalf of Food & Water Watch, the Center for Constitutional Rights and residents of Jackson, Mississippi, who continue to suffer from decades of lack of investment in their city’s water infrastructure. The most recent, high-profile example of that city’s struggles came in 2022 when the area’s largest water treatment facility was overwhelmed by floodwaters, causing plant failure — leaving 160,000 people without safe drinking water. PHRGE’s report emphasized economic and racial disparities in water access and quality in the United States, including through the example of Jackson residents, of whom 80 percent are Black and about 25 percent live in poverty. In November, for the first time ever in a US review, the UN Human Rights Committee flagged the issue of clean water in its concluding observations and recommendations; based on PHRGE’s report, it noted that the country should “ensure access to safe and clean water for its population.”

In another report last fall, to the UN’s special rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, PHRGE attributed discrimination in water access and affordability to “a systemic failure to enforce federal environmental justice commitments on decision makers at all levels of our nation’s water systems” that is “compounded by the absence of information transparency.”

Parched for Particulars

Davis has experienced the lack of information firsthand. In 2019, she and her co-researchers, including Northeastern Law students, set out to study water affordability policies in 12 Massachusetts cities. They had four simple questions: What policies were in place? How many people benefitted from the policies? What consequences did people face for non-payment? Was demographic information collected on the issue? But city administrators often couldn’t even accurately say who might have answers to the queries.

“We found it practically impossible to get information about what utilities’ policies were in this area,” says Davis. “The information isn’t available in any kind of standardized way, not just for researchers but also for the utilities themselves to gauge what kind of programs would be best suited to address affordability issues. As far as we can tell, they just don’t know.”

Ultimately, through Freedom of Information Act requests, Davis and her team obtained some high-level data. They found that none of the 12 cities offered discounts on water bills based on people’s income alone (instead, discounts were available to seniors or people living with disabilities) and three cities offered no discounts at all; four — including Boston — used water shutoffs as a penalty for non-payment; five communities converted outstanding water bills to tax liens that could ultimately lead to foreclosure; only three cities offered payment plans to customers who fell behind on their water bills; and none of the cities collected demographic data about who was having trouble paying their water bills.

Only a handful of states currently require utilities to track the number of water shutoffs and shutoff notices and where they are occurring. Massachusetts may soon be one of them. Earlier this year, PHRGE worked with Massachusetts State Senator Becca Rausch ’04 to introduce legislation that would require public and private water utilities in the state to file quarterly reports providing the number of shutoff notices, actual shutoffs, lien referrals and bill repayment plans and the types of assistance plans being offered to customers.

Rausch co-sponsored the bill, and law student Walker testified in support of it at a hearing. “Those facing the highest rates of water shutoffs are some of our most underserved communities, including poor households and Black and brown communities,” Walker said at the time.

Rausch says PHRGE’s work on the bill is an example of how university research can be converted into action. “It’s too easy for academic work and scholarship to get lost,” she says. “This is a really beautiful example of how academic work and intellectual rigor and scholarship can move the needle and change social structures and systems.”

Massachusetts State Senator Becca Rausch ’04

Photo by John Soares

Academic work and intellectual rigor and scholarship can move the needle and change social structures and systems.

The ultimate solution, says Sanea Lamas ’24, who helped write the bill with Rausch’s staff, including then-Director of Legislation and Policy Jaime Watson ’21, “would be to stop water shutoffs. If you can’t afford a water bill, you shouldn’t lose access to water. But, thinking in smaller steps, we need to get the data to know what sort of problem we’re looking at.”

“By requiring water utilities to report critical data on water shutoffs, we are laying the groundwork for more effective water policies,” Lamas wrote in an op-ed in CommonWealth last spring. “Some of these policies would include developing assistance programs for low-income individuals and ensuring that these programs are communicated to consumers.”

Stream of Information

Sanea Lamas ’24

Photo by John Soares

By requiring water utilities to report critical data on water shutoffs, we are laying the groundwork for more effective water policies.”

So far, PHRGE has published eight reports on the human right to water, including a 2020 report about shutoffs during the COVID pandemic and “Data on Tap: Realizing Human Rights through Water Utility Reporting Laws,” which Jacob Hayward ’23 authored in 2023. That report, which mentions the pending legislation in Massachusetts, links the human right to water to the human right to information and reflects PHRGE’s rights-based approach to advocacy. “Information is so important to all of our other rights,” says Hayward. “How can we track inequality and discrimination without it?”

Through its written research — and its submissions to and advocacy before United Nations experts — PHRGE acts as a bridge between community groups and international governing bodies, says Mary Grant, director of Food & Water Watch’s Public Water for All campaign.

“They bring their legal expertise and knowledge of these international processes that can be hard for regular folks to engage in,” she says. By partnering with people in Jackson on the submission to the UN Human Rights Committee, for instance, they are “expanding the capacity” of local players. “That shows their commitment to centering the voices of people impacted directly.”

Awareness of problems with the supply of water is growing, in part because the impacts of climate change — including drought — are becoming ever more difficult to ignore. Water rates are also on the rise, as cities try to address the challenge of crumbling infrastructure with less funding from the federal government. “More people are realizing that it’s not just a given that water is going to be cheap and available to everyone,” Davis says. “We need things in place to ensure there’s equity — that water is treated as the human right that it is.”

Hayward says viewing water through a human rights lens reveals how dysfunctional US water systems are. “In America, there’s an idea that if you don’t pay for something, you shouldn’t get it,” he says. “But the whole point of a human right is you’re supposed to get it.”

About the Author

Rebecca Beyer is a freelance writer and editor in the Boston area.

Share

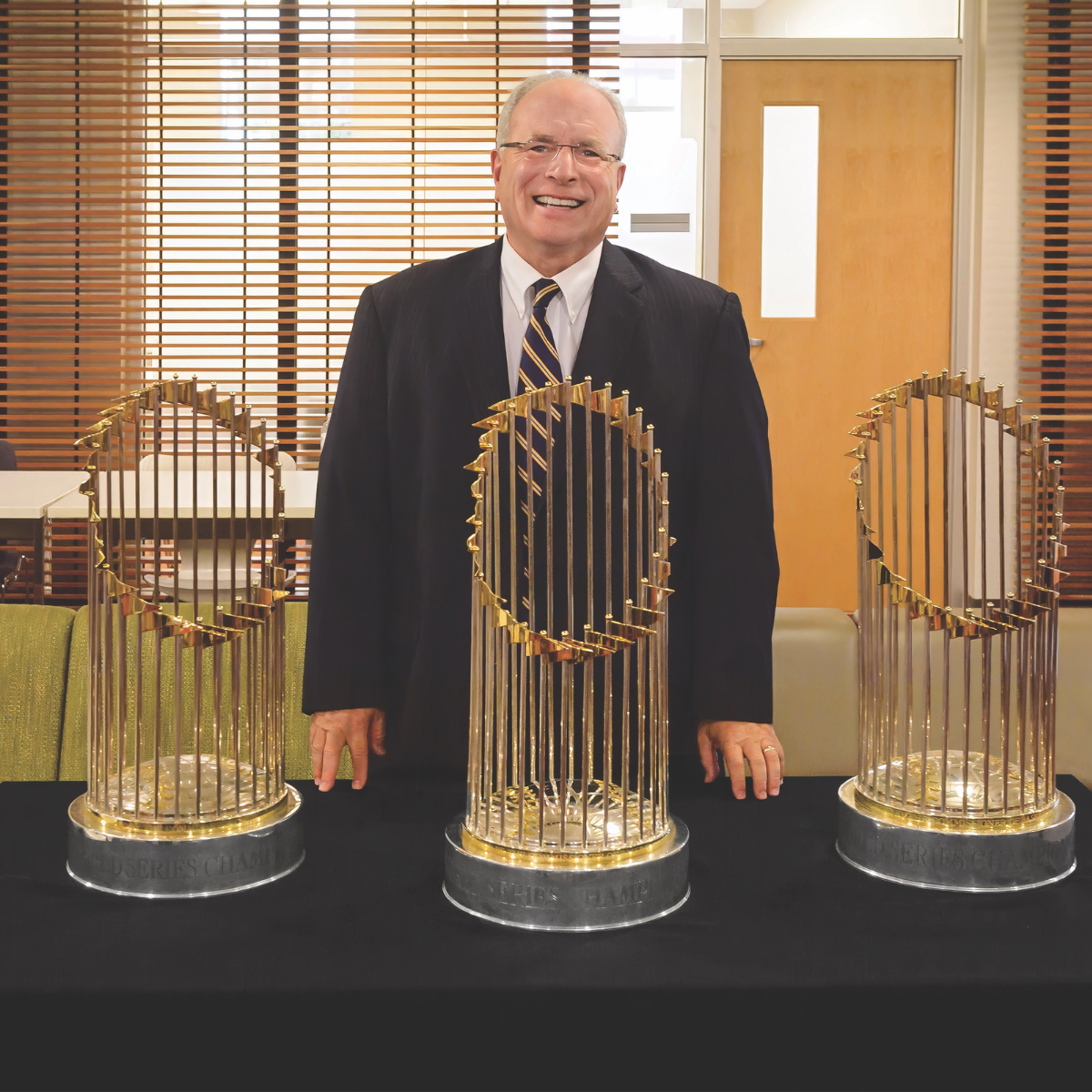

Professor Emeritus Roger Abrams, who served as dean of Northeastern Law from 1999 to 2002, passed away on November 12, 2023, in University Park, Florida, after a long battle with cancer. A prolific author and leading authority on sports law, labor law and legal education, Professor Abrams retired from Northeastern in 2018. Professor Emerita Mary O’Connell ’75 reflects on Professor Abrams’ contributions and camaraderie

More than 240 graduates and friends were welcomed back to campus for a weekend of fun and friendship on October 20-21, 2023, as we celebrated Reunion and Alumni/ae Weekend.

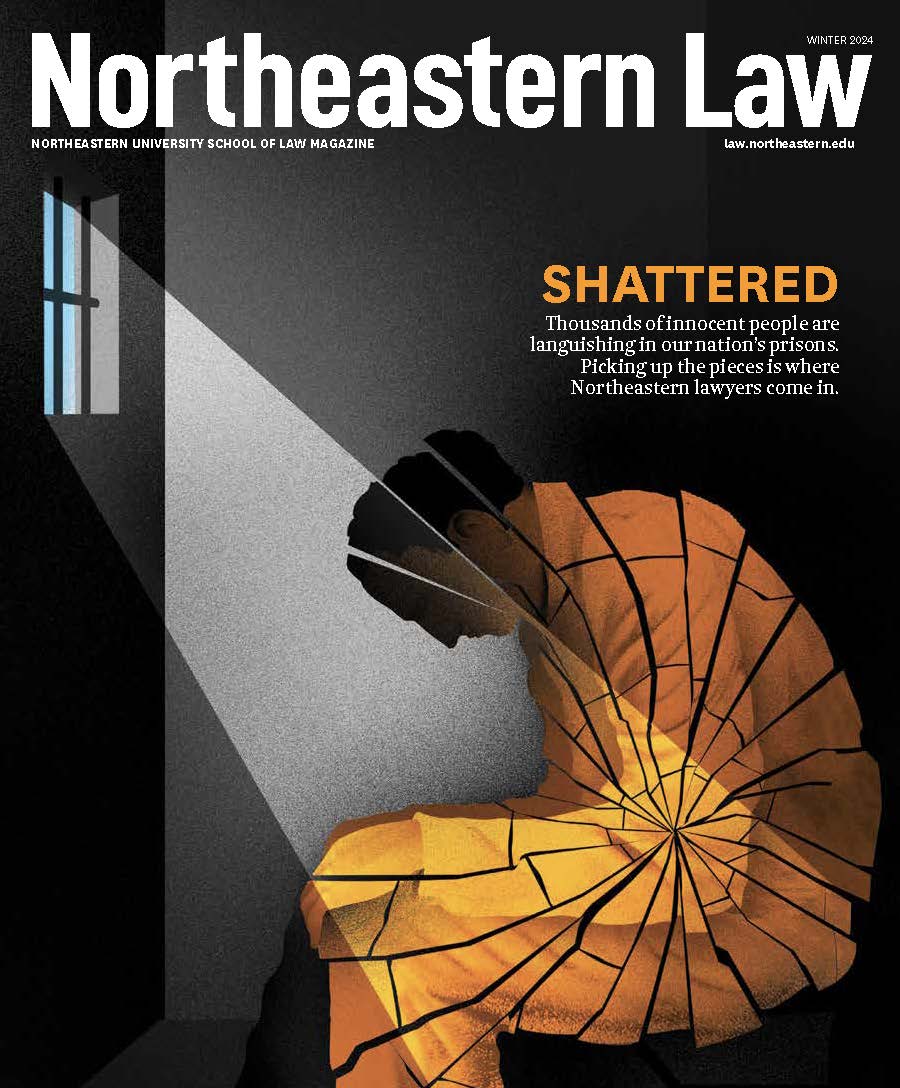

Thousands of innocent people are languishing in our nation’s prisons. Picking up the pieces is where Northeastern lawyers come in.